Durga: Symbolism, Social Change, and the Continuum of Life

Every autumn, as the sound of the dhak fills the air and clay idols of Goddess Durga rise from riverine clay, a familiar story is retold — of a warrior goddess who slays the buffalo demon to restore cosmic balance. Yet Durga is far more than a mythic figure frozen in time. She is a living cultural symbol, layered with meanings that trace humanity’s journey from prehistoric matriarchal societies to patriarchal agrarian civilizations, from fertility cults to state religion, and from local village deities to pan-Indian goddess traditions.

To understand Durga in her fullness is to read the story of human civilization itself — inscribed not in texts alone but in symbols, rituals, and seasonal rhythms.

From Vegetation Spirit to Mother Goddess

In the earliest phases of human society, when subsistence depended on foraging, communities across continents ‘saw’ the “vegetation spirit” — a symbol of nature’s regenerative power. With the advent of agriculture and the domestication of cereals such as barley and corn, this spirit evolved into the “corn spirit”, and eventually into a corn god. *11

This conceptual evolution reflected a deeper association. The fertility of the soil and the fertility of women were perceived as parallel forces. Both nurtured life from within, both transformed seed into sustenance. The emergence of the Mother Goddess — the archetype from which Durga would later emerge — was the natural culmination of this worldview. Across early societies, fecundity, growth, and continuity were personified as female.

Since the ancient humans could not really understand as to how a ‘baby was born’ and as to how exactly at a point of time in cycle trees bore fruit or corn sprouted – they related the power of a Mother with the Nature — which was there but not understood and thus both magical– and must be dicated by some unknown entity -which we may now term as ‘divine’ to keep the life going..

Harvest, the Buffalo Demon, and the Decline of ‘Mother Right’

Durga’s annual worship during autumn, coinciding with the harvest, mirrors the agrarian calendar and the cyclical nature of agricultural life. Yet one of the most central episodes in her mythology — the slaying of Mahishasura, the buffalo demon — carries meanings far deeper than the literal.

Some historians and anthropologists read Mahishasura as an allegory for a transformative shift in human history: the introduction of the cattle-drawn plough. Prior to this technological leap, women were often the primary cultivators, wielding the hoe. With the plough came men’s increasing control over agriculture — and with it, the erosion of matriarchal/ matrilineal structures.

(Even till date in some parts of Bengal local rituals symbolizes the women protests against the plough drawn cultivation. On a autumn morning a farmer would arraive at the dorr step of a family with his two bulls with plough. And the eldest woman of the home would after prrforming some rituals would symbolically take down the plough from the cattle. In my my child hood I had personally seen such rituals at my home. Besides still there are some womanly rituals where women do not take any food born out of ploughdwan cultuvation- like Sabitri Brata etc)

** In this reading, Durga’s triumph over the buffalo demon becomes a symbolic protest of womanhood against its displacement from centrality in social and agrarian life.

The buffalo itself is a charged symbol. In Indian mythology, Yama, the god of death, rides a black buffalo, black representing the unknown journey beyond death. Mahishasura’s form may thus embody death itself — and Durga’s victory over him signifies not merely conquest over an enemy but the triumph of life over death and the continuity of the food cycle.

The association of death and renewal is echoed across civilizations.

In ancient Egypt, the Ankh — symbol of eternal life carried by the fox headed God Anubis or Eagle headed God Horus— was linked to female power and often placed near mummies and tombs to signify that life conquers death. Female symbolises the continuity of life , the journey of a life to eternity– death being the only a passig phase. The egyptian pilosophy was similar that of Hindu philosophy of life and in other words mother power– Matri shakti.

(If you closely see the female symbol’ in the modern day medical / biology world you will see the Ankh in a shorter form.) This female symbol of modern medical / biology on represents the Matri Shakti– the power to defy death and help continue the life on this planet.

Fertility rituals from India to Greece included the ritual sacrifice of a man — a king, priest, or consort — whose symbolic death mirrored the sowing of seed into the earth.

While in our Pouranik stories the death of powerful husband and his revival ( for example Nol Damayanti, Sabitri Satyaban etc) symbolically represent the annual fertility cycle, the story of ancient Mediterranean characters Adonis and older story of Mesopotamian character Tammuz are comparatively more clear in their symbolism.

For exmple Adonis was supposed to return from the underworld (in a sense death) for part of the year — the mythic explanation for spring and summer when vegetation flourishes, and autumn and winter when it dies. His death and return reflect the yearly cycle of plant life — death in winter, rebirth in spring.

On the other hand, Tammuz also spends half the year in the underworld, and his death brings the dry, barren months, while his return marks the revival of life and fertility. His dying and rising mirror the annual death of plants and their rebirth after rain.

As D.D. Kosambi wrote these rituals represent “the death of the male principle at the hands of the female principle to sustain the cycle of life.” *1 This motif resonates deeply with the Durga–Mahishasura narrative.

Tryambake: The Three Eyes and Cosmic Balance

Durga is also known as Tryambake, “the three-eyed one,” and each eye carries symbolic meaning:

- The left eye, associated with the moon, represents iccha (desire).

- The right eye, aligned with the sun, represents kriya (action).

- The third eye, symbolizing fire, represents jnana (knowledge).

(Interestingly Egyptian God Horus eyes are symbolically same to that of Durga and Shiva. When asked AI said while the Egyptian God Horus is the god of the sky, kingship, and protection, his right eye represented the sun and his left the moon)

Together, these three forces sustain the cosmic order. Creation, preservation, and destruction — the triadic rhythm of existence — are held in balance within Durga’s gaze. This dimension underscores her role not merely as a warrior or mother but as a cosmic principle regulating the cycle of being itself.

The Lion and the Archetype of the Protector

Durga’s lion mount is more than an emblem of ferocity. Across ancient cultures, lion- and cat-associated goddesses — from Egypt’s Sekhmet to Anatolia’s Cybele — symbolized fierce protective energy and cosmic power. The lion represents untamed strength and royal authority, qualities Durga harnesses as the force that subdues chaos and upholds order.

The Iconography of the Ten Hands

Durga’s iconography — her ten arms each bearing a weapon or symbol — encodes a wealth of philosophical ideas:

- The conch (shankha) embodies pranava, the primordial sound Om.

- The bow and arrow signify mastery over kinetic energy.

- The lotus, rising unstained from mud, stands for purity and self-arising potential; in Durga’s hand, it is only partially open, indicating assured success yet ongoing endeavour.

- The sword represents knowledge, capable of cutting through ignorance.

- The trishul embodies the three gunas — sattva (spiritual), rajas (mental), and tamas (physical) — whose balance sustains creation.

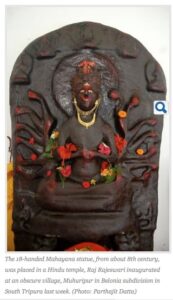

This multiplicity reflects the goddess’s manifold powers and responsibilities. In Buddhist traditions, Durga reappears as Chundi with 18 arms ( Refer the Deity as Rajeswari Temple in Jolaibari area in South Tripura), or as Tara, demonstrating how goddess archetypes transcend sectarian and cultural boundaries.

Shakti, Tantra, and the Goddess of War

Durga is the embodiment of Shakti, the primal energy that animates the universe. Her cult found natural expression in Tantric traditions, where offerings of meat, alcohol, and blood contrasted sharply with the ascetic ideals of Vedic orthodoxy. She is both the creative and destructive principle — nurturing life and annihilating its threats.

Her martial aspect is equally significant. The Ramayana recounts how Rama invoked Durga before his battle with Ravana, highlighting her association with statecraft and victory.

( Only recently I saw a video clip where Nrisinghaprasad Bhaduri says, Ram did not perform the Okal Bodhon , it was Brahhmma who offered the Puja at night for Ram’s victory. Since it was performed at night it instead of day, it was called Okal Bodhon)

Scholars have traced aspects of this martial character to southern goddess traditions, possibly linked to a deity known as Karavi, worshipped with buffalo sacrifice and fierce rites. Over time, these local and regional traditions coalesced into the composite figure of Durga in the pan-Indian imagination.

Durga as the Eternal Principle of Renewal

Durga, then, is not merely a mythological figure but a symbolic repository of human memory and social transformation. She embodies the transition from matrilineal to patriarchal societies, the shift from foraging to agriculture, the intertwining of fertility and mortality, and the cosmic balance of desire, action, and knowledge. Her annual worship marks not just the harvest season but the enduring rhythm of life triumphing over death.

In this light, Durga is more than a goddess who rides a lion and slays a demon. She is a profound cultural idea — one that encapsulates humanity’s deepest reflections on life, death, power, and renewal. As devotees gather each autumn to welcome her, they also reaffirm an ancient truth: that life persists, that balance endures, and that the primal energy of the Mother remains the sustaining force of the cosmos.

*11 Dr Sujit Chaudhuri -Prachin Bharotey Matripradhanyo

*1 D.D. Kosambi – Myth and Reality

* Sir James Frazer -The Golden Bough

** Friedrich Engels – “world-historic defeat of the female sex”, The Origin of the Family, Private Property and the State.

|Also Read : 149-year-old Durgabari Puja, initiated by kings, funded by successive govts, remains Tripura’s key attraction |

|Also Read : Tripura Tourism sees remarkable 64% growth in 2024: Sushanta